I would never call myself a landscape photographer, I suppose partially because Mr. Adams made it about arduous hikes to secluded vantage points by intrepid adventurers, and I’m just not a hiker (ask anyone). A portrait during a conversation in a cafe is where I’m more qualified, or capturing a meaningful moment in someone’s home or studio. I think also I was always disappointed with my attempts at landscape because everything ended up so much smaller than I remembered it being when I set my camera and make the exposure.

I would never call myself a landscape photographer, I suppose partially because Mr. Adams made it about arduous hikes to secluded vantage points by intrepid adventurers, and I’m just not a hiker (ask anyone). A portrait during a conversation in a cafe is where I’m more qualified, or capturing a meaningful moment in someone’s home or studio. I think also I was always disappointed with my attempts at landscape because everything ended up so much smaller than I remembered it being when I set my camera and make the exposure.

I’ve discovered, however, that there is endless information in an image if you look closely enough. In a portrait, this often means things to remove – nose hairs, pores and blemishes, dandruff, food particles. But in the landscape it means dew drops and a million leaves and teeny tiny automobiles with little people inside! Make a print big enough and the landscape is the real-life version of a model train layout. The moment the shutter clicks the story is being told forever.

This is my landscape photograph.

It is not a remarkable sunset with surreal colors and God’s rays of light. Those are easy. “Lease a phone and be there”, Mr. Capa might say today.

This unremarkable “landscape” is easily dismissed – but I see the verge of a storm, on the edge of the West, past the shore of a river, with a sliver of town, at the end of a day. Witnessed and photographed from a 22nd floor private office, framed (literally) behind window glass that reflects the interior lights, this view is protected and private, experienced in person by only a well-heeled elite (and the random artist guest). These seem precisely the criteria for the great landscape photograph per Mr. Adams and his practitioners. The hike, to my relief, included validated parking, two elevators, and a slightly tepid espresso.

Posted on

Wednesday, September 2nd, 2015 at

7:02 PM

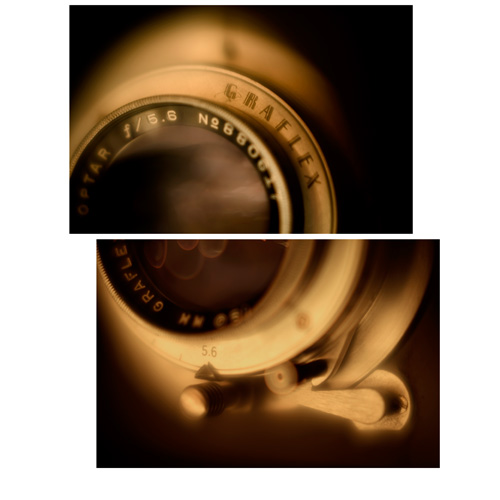

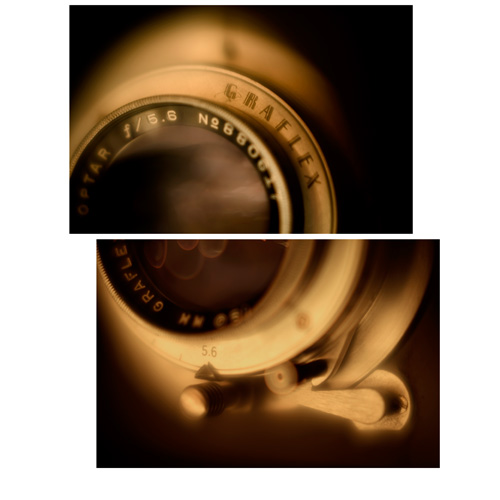

What a long and grueling trip it’s been from a film camera kit that worked perfectly in the late 90s to a digital kit that finally works in 2014.

The goal for this bag has been a lightweight all-in-one-bag 2-camera documentary kit that I could use to produce most documentary-style available light assignments (commissioned and personal) without compromising image quality. Trying to replicate my film kit: 2 M6s with 21mm, 35mm, 50mm, and 90mm Leica lenses in digital has taken 15 years. Everything up to that point was a big case of Canon DSLRs and lenses for pro work, and increasingly disappointing point & shoots (Canon, Nikon, Fuji) for carry-around. That part was partially solved with the Olympus E-20 and then eventually the E-P1, but the Micro 4/3 sensor felt inferior, even though the images looked great.

Then in 2010 I bought a new M9 with 2 lenses: a 35mm f2 Summicron and a 24mm f2.8 Elmarit, adding a 50mm F1.5 Zeiss ZM and finally a 75mm f2.5 Summarit. The 24 was a conscious decision to avoid the distortion of the 21 since I mostly shoot people, but I felt pretty early on that it was just never quite wide enough. I also longed for a second body, but at $6K for another M9, I was pretty sure that was not going to happen.

Every year I watched Fuji and Olympus try to out-trick each other, but am a confessed full-frame snob and couldn’t commit to APS-C or M4/3. Each new Fuji dashed hopes that they would get it perfect which it would have to be to go to a smaller sensor, and each new Olympus was superb – but still 4/3. And then out of the blue (for me anyway, I never thought of Sony as pro still equipment) came Sony with the a7 and a7r.

And so today, after 2 months of testing, my kit is complete. The a7r with a Fotodiox adapter and a Voigtlander Scopar 20mm 3.5 gets me the wide angle I’ve been missing (no way to get acceptable results from super-wide M-mount glass), and a Voigtlander VM adapter for the 75mm which works beautifully. The 35 and 50 work mostly on the M9, except when extremely low light requires they jump onto the a7r. All manual focus, all with the soul of working with rangefinders, but with a couple of welcome perks from the more digital Sony. Files and colors are very compatible, and if needed the Sony will take all my other Nikon glass too.

I use an Olympus LS-10 digital voice recorder for field audio, Apple 11″ Air for location downloads and basic file prep, which along with the requisite Moleskine, spare batteries and cards and Passport Color-Checker all fit very manageably into a compact and innocuous Artisan & Artist “Sebastio’s Reporter Satchel”.

It’s been a decade-and-a-half search to assemble this collection of gear that works so perfectly for my needs, and at a fraction of the all-Leica approach. I really am breathing a sigh of relief, and looking forward to the next assignments.

UPDATE July 2, 2014:

I’m really enjoying this kit. The ability to work with two cameras with complementary lenses – the 20 + the 50, or the 35 + the 75 – just feels right, like I’m prepared for what may show up and with the flexibility to make different images of the same situation. By chance, I’ve been shooting a fair amount of local, small-venue concerts and found the Sony to be amazing in low-light (no surprise – that’s what everyone reports). I do find the 75mm a little short for performance work, however. So I’ve added a recent purchase – a 135mm f2.0 AIs manual focus Nikkor which replaces the 75 for performance and portrait shoots. The F2.0 is great for low-light, the 135mm reach is much better if I can’t get close, and wide-open for portraits it’s amazing. The lens is heavy and the built-in sliding hood is loose and uncontrollable – but those are the only drawbacks. I haven’t shot a 135 since the late 60’s and this focal length is refreshing and useful.

In The Bag – v2.0

©2014 Mark Berndt | All Rights Reserved

Posted on

Tuesday, May 27th, 2014 at

11:49 PM

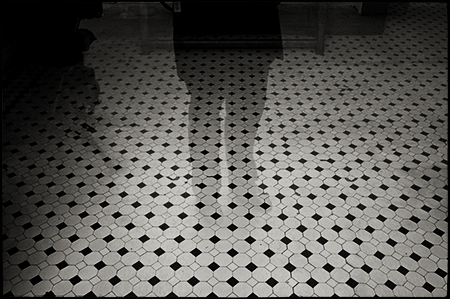

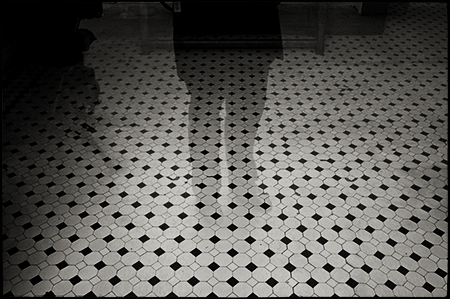

I work at home, and I suppose I often go out just to put myself somewhere where I will find the day’s pictures. I don’t go searching for them, but just to make myself available to see. They’re hiding everywhere – and the surprise is in not knowing what they’ll be or where they’ll show up.

In the beginning there’s a nearly imperceptible tug on my eyeball that suggests there’s about to be a photograph. It’s not spiritual, like a whisper or hair standing up on the back of my neck. It’s more like a speck of grit in my eye that makes me blink, squirts a little adrenalin into my system, and causes my right hand to slide around the right side of my camera and flip the ‘on’ switch.

It’s always hanging there, 50mm lens, f/stop wide open, focused at infinity, ISO at 160 unless I’m inside, and the shutter speed set, as leave the house, to something appropriate for the day’s conditions. Without looking, my left hand slides to the lens and I might rotate the focus ring by feel a little bit, channeling some future distance-to-subject setting.

I’ve noticed that the process of making a picture works like this for me:

First, I become aware that there’s a picture nearby – a little story disguised as everyday life. It could be a movement, a patch of light, a reflection, a pattern or a face. Once I find it, I make an initial intuitive exposure – quick, before it gets away. Sometimes that’s all I get, but if there’s an opportunity, I’ll try to do better – adjusting my position (no zooms), camera angle, framing, double-checking focus and exposure. I might get another 2 – 5 exposures.

The rear screen on my camera is set to off by default so there are no pictures popping up while I’m shooting. This allows me to make the image come together in the viewfinder, rather than looking afterwards to see what I shot.

Most often the first and the last images are the ones – the first for spontaneity and authenticity, or the last for the refined composition and exposure. It’s exciting every time, and just 50% of the image – the darkroom still to come…

©2014 Mark Berndt | All Rights Reserved

Posted on

Thursday, May 22nd, 2014 at

4:59 PM

I use photography to order my world, to segment and synchronize visual elements into little short stories about light and line and color.

I think these arrangements have an aesthetic and a personality that would go unnoticed if this little black border didn’t excise it from the surrounding chaos and celebrate its proportion and balance.

The challenge is not in the seeing, but in making the time to stop, consider, refine and preserve – and in recognizing when the effort was successful, or not.

The older I get, and therefore the longer I’ve been doing this, you’d think the finding and preserving of the little stories would be getting harder. But you know, I haven’t seen anywhere near ‘it all’ yet, and the world is a fascinating and constantly changing place that keeps sparkling up surprises that I want to capture – you know, literally put in my little trap and take home and mount on my wall.

And so the challenge is in making a picture that hasn’t been made before, that uses and stretches my understanding of what constitutes a photograph and satisfies my lust for glittering 2-dimensional gems by stretching and breaking the conventional laws of composition to create the most elegant balance of weights and colors and shapes. That exploration often results in pictures that are more about balance than subject – and that’s when the fun really begins. I search out opportunities to make photographs of light, and of weight, and of relationship, and of movement – but perhaps not of any ‘thing’ in particular.

And I feel most accomplished when I make a photograph that is not a picture of the object I’m photographing, but of the moment itself.

© 2014 Mark Berndt | All Rights Reserved

Posted on

Tuesday, March 18th, 2014 at

4:57 PM

Dave (Ludwigs) left the studio on Troost for a shoot, and I was working in the darkroom when Cherie told me an art director had called needing a COB shot of a wheelchair – immediately. She called to have a chair delivered from Abbey Rents while I set up the white seamless and rolled Dave’s 50-pound hand-welded plumbing-pipe-and-tracing-paper soft box over, fired up the Balcars, slapped a Polaroid back on the RB67 with a 50mm lens, plugged in the sync cord and shot an exposure test.

3 minutes after the chair arrived the first (and only) exposure of the chair on 665 was clearing in sodium sulfite, followed by a quick rinse and blast from the low setting on a hair dryer. Smacked into the Beseler 45 MCRX a little damp I printed onto 8×10 RC paper with some cards positioned on the paper to mask out the studio. Followed by a little bleaching around the edges of the wet print with q-tips to ensure a clean cut out, I ran the hair dryer again and we messengered the finished print to the agency – an hour after the call.

Digital Schmigital!

I always liked the shot and intended to make a proper silver print someday – but the coated pos part of the Polaroid from 1974 is the only copy that remains.

A lot has changed since then – gone or scarce – Abbey Rents, Polaroid, Balcar, Mamiya, most chemical darkrooms, and unfortunately my incredibly significant mentor, employer and full-fledged-university in commercial/advertising photography David Ludwigs – may God rest his soul. Although it may be lost on new photographers, this story is about CREDIBILITY.

It’s about the part of photography that didn’t change when cameras went digital. It’s about problem solving and creativity and meeting deadlines and making a unique image of a mundane subject and about calling all that up on command – no excuses – which is what being a PROFESSIONAL is all about. “Professional Photographer” – a term that today gets you little respect and even less remuneration because “…everyone is a photographer”. Well you know what – they’re not.

David Hurn said “… you are not a photographer because you are interested in photography.” I say “You are not a photographer just because you take pictures.”

I wanted to share the story about this image because, in addition to the multi-thousand-dollar film shoots and big-production projects I’ve been responsible for in my life, this seemingly insignificant chicken-salad-out-of-chicken-shit still photo that I shot in 1974 tapped my skills, built my toolbox and contributed just as much to my life as a photographer and an artist.

© 2014 Mark Berndt | All Rights Reserved

Posted on

Monday, January 27th, 2014 at

1:26 AM

I confess I’m an old school photographer, even though I’ve been doing 99% of my work digitally since 1994. I shoot at film ISOs. I shoot at manual film advance frame rates. I love my tripod. Half my cameras don’t autofocus. And I shoot with prime lenses.

I have always owned and used zoom lenses for commercial assignments. For years I avoided a 24-70mm zoom lens although I had a 70-200mm and 16-35mm, but eventually I ended up with the coveted ‘triumvirate’. They were a necessity, not a choice, for when I needed to be at a focal length not available as a prime – when the shot the client needed dictated the camera position and I needed the lens to compensate. It was my concession to being professional – to being able to make any client’s picture no matter what.

For personal work (and these days more and more of my commercial work is ‘personal’) I carry a rangefinder camera with me all the time, and use it for almost all of my normal-to-wide angle shooting. The bright lines for the 35mm and 50mm lenses have become etched into my cornea, and I’m working on the 28mm. There’s a heads-up display framing everything I see – I can’t help it.

PRIME LENSES WORK

Last year on an assignment with a 24-70, I did a test. I shot at a number of in-between focal lengths and found that the images that worked best were shot at the prime focal markers on the lens, not at 23mm or 46mm or 67mm. So in my recent DSLR brand shift, I’ve eschewed zooms and built this new kit 100% with primes – 20mm, 35mm, 50mm, 105mm, 180mm. Although occasionally I find this a little scary on a commercial shoot, I’m totally at ease with fixed lenses. I use less equipment to make better pictures. I avoid big, heavy, conversation-starter tools so I can disappear better.

I am working simply to capture more complexity – in my subjects and in my compositions.

SLOW CRAPPY ZOOMS

Significantly for new photographers today, the 50mm “normal” lens packaged with film SLR bodies back in the 20th century has been replaced by the slow crappy zoom. Most photographers who buy a camera-with-lens kit don’t know about lenses yet. They don’t understand f-stops; that cameras need light to autofocus; that there are compromises when shooting at the high ISOs mandated by a slow zoom. They often don’t know what a “prime lens” is, and they haven’t yet learned how the choice of focal length impacts their image. They use the zoom to crop their snapshot in the camera, and miss the much more significant part – how different lenses draw the world.

Zooms outnumber primes in the major camera brand lens lines. They represent that unfortunate bi-product of the digital revolution – multi-tasking – and the novice’s quest for a do-everything picture-machine that fits in your pocket, makes building-sized prints and shoots pictures where there’s no light. Photographers complain about weight, about having to carry things, and about forgetting that thing they really needed. They want to work small, expect big results and want every option available so they don’t have to plan (oops, I mean so they can be spontaneous and ‘creative’). There is no such device, but the equipment manufacturers happily feed the myth with slower zooms, image stabilization (which does NOT make the same picture as a faster lens), distortion correction software and plastic materials recognizing that there are profits to be made along the path to prime lens enlightenment.

This is not to say that, in the hands of a knowledgeable user, the zoom is not an invaluable tool (sometimes only a 38mm lens will do), but for all but the most dedicated new photographer it delays true understanding with an illusion – a cropping device masquerading as intentional lens selection.

TRY IT, YOU’LL LIKE IT

Canon and Nikon, and most of the big brands, make a 50mm prime lens with a relatively fast aperture (f1.8 or f2.0) for about $100. On a full-frame camera, that’s a “normal” lens. For crop-sensors it’s a portrait telephoto. If you want a “normal” for a crop-sensor you need a 28mm lens which might be a little more expensive and not quite as fast. Used lenses are usually less.

That simple lens will allow lower ISOs, faster shutter speeds and render more beautiful out-of-focus areas in your images (I really HATE that “b” word for this effect) than any zoom at a fraction of the weight, size and expense. You’ll carry your camera more, engage with your subjects differently, and launch the gestation of the first focal length imprint on your pre-visualization cortex!

Ok – I made that last part up (I think).

SAVE THE PRIMES

Or how about this – if we don’t buy prime lenses they’ll go extinct. It happens. Kodachrome, the ‘real’ Tri-X, Polapan, Rodinal, Panatomic-X, flash bulbs…

Can you afford to spend a hundred bucks to revolutionize your photography? Can you afford not to?

© 2013 Mark Berndt | All Rights Reserved

Posted on

Wednesday, September 18th, 2013 at

9:15 PM

A glimpse, a moment, a memory, a sign, a problem, a solution, a wish, a love, familiar, unknown, remarkable, mundane, to report, to comment, to praise, to oppose, friend, foe, history, future …

The reasons for making pictures are as varied as the photographers who make them.

I started making pictures as a kid, using my Dad’s Brownie Hawkeye. I liked the sound of the click, looking down into the fuzzy viewfinder. I couldn’t wait to see one of my pictures in the stack of deckle-edged prints that came back from the drugstore. My early photographs mimicked my parents’ – family scenes, friends and pets. No thoughts of career or genre or copyright – just a confirmation of a moment past and the satisfaction of making something I could hold in my hands.

I’d have to say that I’ve evolved through the years – first learning photography, then photography-the-hobby, the early commercial work, then the well-funded hobby, then back to what I like to think of as more enlightened commercial work plus artful personal projects – and today I’ve come full circle. I knew it intuitively in the beginning and now it’s a relief to return to that clearly defined purpose – confirmation of a moment past, and the satisfaction of holding something in my hands that I made.

Today I try to approach my images with this intention: communicate clearly, compose precisely, finish professionally, but capture and keep the imperfections that give them a humanity. I’m a perfectionist about the process, but I want to impose minimal impact on the content. I prefer to observe, not direct. I’m a digital zealot who hates digital-looking images.

And I print – because for me the print is the reason I photograph. The print keeps me honest. I create from an empty frame that thing that I hold in my hands.

Why do you make pictures?

Have you thought about it lately? Do you remember why you started and how making a picture felt in the early days? Have you put that into words – written it down? Make some time to sort this out, to remember and to reconnect. Write a short paragraph, a sort of mission statement to remind you why you make pictures. Then let it inspire you by reading it before your next shoot – or your next 10. And see the difference it makes.

© 2011 Mark Berndt | All Rights Reserved

Posted on

Friday, November 18th, 2011 at

9:50 PM

I would never call myself a landscape photographer, I suppose partially because Mr. Adams made it about arduous hikes to secluded vantage points by intrepid adventurers, and I’m just not a hiker (ask anyone). A portrait during a conversation in a cafe is where I’m more qualified, or capturing a meaningful moment in someone’s home or studio. I think also I was always disappointed with my attempts at landscape because everything ended up so much smaller than I remembered it being when I set my camera and make the exposure.

I would never call myself a landscape photographer, I suppose partially because Mr. Adams made it about arduous hikes to secluded vantage points by intrepid adventurers, and I’m just not a hiker (ask anyone). A portrait during a conversation in a cafe is where I’m more qualified, or capturing a meaningful moment in someone’s home or studio. I think also I was always disappointed with my attempts at landscape because everything ended up so much smaller than I remembered it being when I set my camera and make the exposure.